Ed’s Threads 071005

Musings by Ed Korczynski on October 5, 2007Fairchild at 50 still milking the IC cash cowThe 50th anniversary of the founding of Fairchild Semiconductor was celebrated on October 5th and 6th at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. With

Jay Last also in the audience, and with many call-outs to other Fairchildren living and dead,

E. Floyd Kvamme (Marketing) led a panel discussion of

Gordon Moore (R&D),

Wilf Corrigan (Manufacturing), and

Jerry Sanders (Sales). Marketing has really never gotten any respect in the chip industry (unlike at Apple and some software companies), while the other three domains have combined to create the uniquely chaotic culture that is Silicon Valley.

Why do ICs seem to always get cheaper and do more each year? Why do we send manufacturing jobs to other countries? Why are huge egos rewarded in high-tech industries? It all comes from the trial and error experiences of the people who worked at Fairchild Semiconductor in the first ten years of the company’s existence. Driven by a vision, and fueled by caffeine and alcohol, scientists and engineers created new technologies, new companies, and new ways of doing business.

Fairchild Semiconductor was formed by the famous

“traitorous eight” who quit en masse from Shockley Semiconductor in 1957. Gordon Moore explained, ”Shockley was an unusual personality. Someone said that he could see electrons, but he couldn’t work with people.” After trying to get Shockley replaced, Moore confessed, “We discovered that a bunch of young PhDs didn’t have a good chance to displace a recent Nobel Prize laureate.” After first trying to all get hired by another company, they were eventually convinced that they should just start their own company and found funding with Fairchild Camera and Instrument.

R&D was the foundation for everything at Fairchild Semiconductor. Inventing a new industry takes a lot of work, and new devices, processes, and equipment were designed and deployed regularly; at the peak it was “one new product per week.” With intense commercial competition, as long as something works and is reproducible it just doesn’t matter if you know the theory of why it works. “We had a lot of technology that worked but we didn’t understand why,” admitted Moore. Another initial mystery was why technology transfer from R&D became more difficult as the manufacturing people became more technically competent. Eventually, it was discovered that the manufacturing people thought that they would add value by “improving things,” but generally only changed things for the worse. The logic solution to this problem is the “Copy Exactly!” manufacturing strategy of Intel.

Manufacturing semiconductors has always been technically risky and yet like any manufacturing line it must be controlled with a conservative mindset. Trying to conservatively manage risk results in a sort of unique schizophrenia, and has inadvertently accelerated global technology transfer. Wilf Corrigan explained that when he joined Fairchild in 1968 from Motorola, he was immediately struck by the difference in high-volume assembly strategies. “Motorola was very focused on manufacturing excellence, and had thousands of people making automated tools.” In contrast, Fairchild had thousands of well-trained women earning low-wages in Hong Kong. “Using a global approach to drive costs down was part of the legacy of Fairchild,” said Sanders. Moore commented that Intel’s first assembly line using Asian female manual laborers was faster than the then-state-of-the-art automated IBM assembly line, and could rapidly adjust to handle new wafer sizes and package designs. So “outsourcing” has been part of Silicon Valley almost from the beginning.

Sales has always been the vital third leg for the industry. New IC products can break open entirely new lucrative markets, but it still takes someone to go get the order despite problems with manufacturing volumes. Sanders told the story of selling planar transistor against grown-junction transistors by TI, and winning one aerospace contract by putting lit matches to both and showing that the leakage-current went out-of-spec on the TI chip. Kvamm told of selling glob-top packages that failed so easily with a fingernail flick that they were derisively called “pop-tops.” Moore added, “We sold the rejects from our Hong Kong packaging line as eyes on teddy bears.”

Sanders confessed, “When I started with Fairchild, I was single and had no concept of home life. I’d show up at a sales-guy’s house at 7:30 in the morning on a Saturday to start work.” Sanders seemingly has selling in his genes; after 30 years he’s still trying to sell the original AMD mission statement, and during the panel he couldn’t stop himself from making gratuitous pitches for AMD chips. Still, he typifies the “shooting ahead of the target” mindset of a salesman who knows what his customer will need in advance of formal demand. Huge egos are just par for the course, and Sanders proudly recounts signing off on the claimed largest bar bill in Hilton Hawaii history for a global sales meeting. Getting everyone drunk and happy in a group setting was supposedly the only way to keep egomaniacal individuals working together as a team.

The history of the industry is really just the combined stories of individuals, and nearly every classic Silicon Valley success story starts out with a chapter on gross incompetence of top executives at a soon-to-be-former employer. Fairchild drove out

Charlie Spork to create National Semiconductor in 1966. Sanders commented, “When Charlie Spork resigned I was stunned. I said to him you can’t do this, and Charlie just went off on the incompetent corporate management. Charlie said he just couldn’t work here anymore.” When Robert Noyce was passed over to be the CEO of Fairchild in1968, he decided to leave and took Moore with him to found Intel.

The Fairchildren were smart and worked hard, but timing and luck were also keys to success. “The fact that Fairchild started in the technology areas that were the ones that continued—manufacturing use of diffusion, batch processes—was lucky,” admitted Moore. “If you ask me about Intel, I’d say a lot of luck was involved.” Of three different technology and product directions started upon by Intel, only the silicon-gate MOS process was successful. “If it was much harder we might have run out of money before proving it, and if was much easier then others would have copied it,” said Moore.

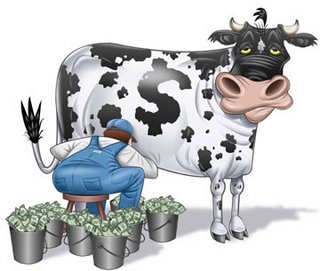

Fairchild ultimately infected the area to be known as Silicon Valley with the culture of the engineer/entrepreneur archetype, stock-options, and high R&D spending. When there was still innovation to be done, this resulted in tremendous creativity and technology growth. With the major innovations in silicon IC manufacturing essentially in place by the mid-1970s—with the exceptions of lithography and EDA—the last 25 years have been mostly about milking the technology cash cow.

At the reception, one of the Fairchildren pitched his new chip design to me and wanted to know if I could hook him up with some financing for a start-up. Old habits die hard, and I’ve been infected with the entrepreneurial

meme so I can relate, but I can’t help feeling that the time is past for chip startups. Too many competitors have evolved to fill all market niches, and IC functionality has seemingly reached a point of saturation such that software now adds the incremental value. The future of bold innovation belongs to software startups like Netscape and Google, while IC folks can really only anticipate more milking of the herd of cows already bred by the Fairchildren. Pass the milking stool.

—E.K.